Near misses: can we prevent or reduce them?

Has it happened to you?

“Whew, that was close!”

“Who’s going to believe what we just escaped?”

Whether at work or in normal living, we all have had close calls – aka “near misses.” Some workers characterize near misses as injuries that didn’t happen. Others might say near misses are precursors of accidents (that is, accidents that didn’t happen). And we all recognized the phrase, “That’s an accident waiting to happen.”

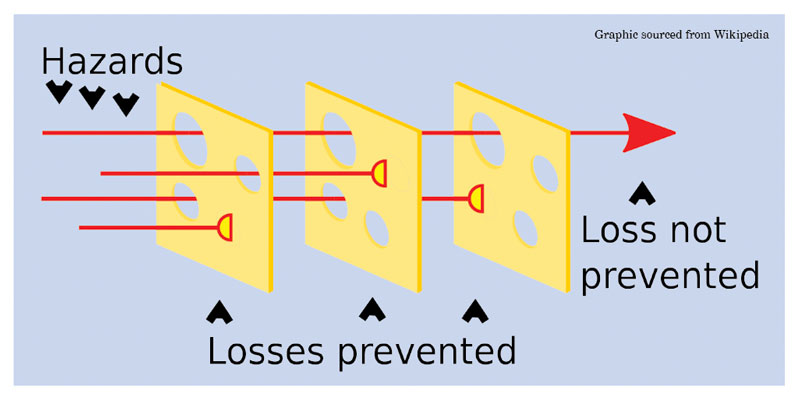

One way to visualize near misses is to use the Swiss Cheese Model. In the model, slices of Swiss cheese – the cheese with the holes in it – are placed on edge, side by side. If you try to thread a chopstick through a hole in the first slice, it will most likely be blocked by a solid portion of one of the other slices and will be stopped from going straight through all of them.

Only infrequently will the chopstick make it through holes in all the slices.

If the chopstick represents a hazard that is moving through different aspects of a work process (the slices), you hope it will be stopped and not result in a bad outcome. In the Swiss Cheese Model, when the chopstick (hazard) makes it through all the lined-up slices, some harm results.

Two near-miss accounts

An article titled “Characterising near misses and injuries in the temporary agency construction workforce: qualitative study approach” was published in 2020. Although the study was based on focus groups and interviews with temporary workers in the construction industry, the results of the study provide some clarity around near misses that are applicable to the fishing industry.

At the outset, the authors draw on the work of earlier researchers that “unsafe acts” and “unsafe conditions” are major contributors to workplace injuries.

Translating this to the fishing industry, we have an obvious example in the linkage between the unsafe act of not wearing a personal flotation device (PFD) and the unsafe condition of cold water. Those who survive immersion in cold water without a PFD – few and far between to be sure – can be said to have experienced a near miss.

I am reminded of an account a young fishermen provided at a past Maine Fishermen’s Forum: he attributed surviving a serious cold-water immersion to wearing a flotation belt. When rescuers found him, he was struggling to hold onto a buoy, too weak and too cold to help the rescuers pull him from the water. Rescuers were able to gaff him by the flotation belt.

The presence (or lack) of policies and safety protocols play into the discussion of near misses.

For example, immersion suits are required for certain fishing vessels depending on where they fish. For many fishermen, the wearing of an immersion suit has meant the difference between survival and fatality; between near miss and heartbreak.

After one northeast fisherman was forced to leap overboard from the stern of his burning boat, rescuers pointed out to him that the back of his immersion suit had been singed by the flames pursuing him. In this example, compliance with a requirement coupled with knowing when to abandon ship saved a fisherman.

In the first account, a young fisherman made an unsafe choice which, by fate, resulted in a near miss not a fatality.

In the second account, the fisherman made the safe choice to be in compliance with the immersion suit requirements – and that made his experience a near miss, rather than a fatality.

The take-away is that near misses happen in many different circumstances.

Reducing the likelihood of a near miss

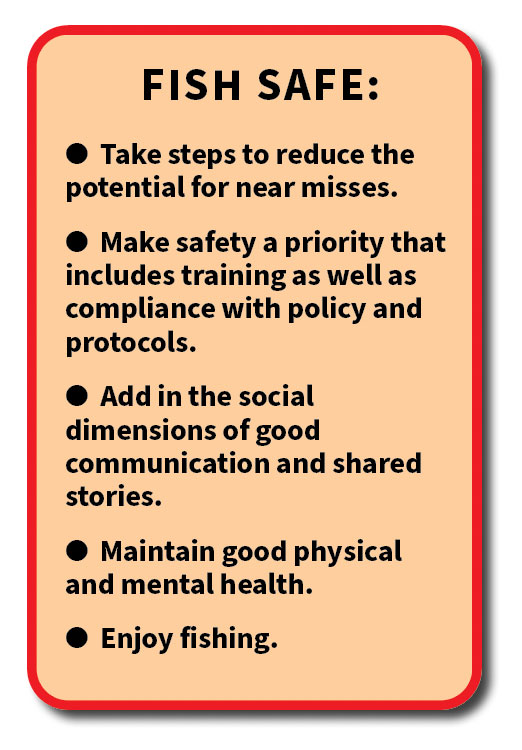

It is important to take steps to reduce near misses: if we don’t take action, the Swiss cheese holes will line up much more often and possibly lead to injury – or worse. Some risk management professionals describe near misses as precursors to accidents, but in the study described above, the construction workers thought of near misses as precursors to injuries. (The distinction being, they explained, that accidents are inevitable – but near misses are preventable or manageable.)

That mindset suggests two things: there are ways to reduce near misses; and we can learn from our near misses.

The authors of the near misses report remarked that their study participants recommended “improved worker hazard identification, jobsite orientation, and awareness to reduce the risk of near misses and injuries.” For us in the fishing industry this brings up training, worksite orientation, and drills. There are several training courses available to fishermen that teach hazard recognition and situational awareness along with proper deployment of liferafts, EPIRBs, etc. Most of these courses teach problem-solving skills and provide practice using these new skills. On board, a captain can provide “jobsite orientation” that includes ensuring that deckhands, apprentices, and sternmen – i.e., whoever is on the boat – know how to drive the vessel; where the fuel shut-off is; and how to make a Mayday call, for starters. On-board drills provided by a USCG certified drill instructor are required for many vessels, and a great idea for the others. (See accompanying schedule for upcoming safety classes sponsored by Fishing Partnership.)

Compliance with regulations, adherence to safety protocols, and making safety a priority are other concrete actions that a manager or boat captain can take to reduce near misses.

A social “culture” where workers “watch out for everybody who’s around” was mentioned by workers as a near miss reduction strategy. In the fishing industry at large, this Good Samaritan approach is very prevalent. It should also play out at the level of the individual boat, where good communication among the crew encourages everyone to bring up hazards they notice, and then work together to solve the issue.

Clearly physical and mental health – including good nutrition and adequate sleep – will reduce or protect against near misses. Weakness or poor balance, for example, make a person prone to near misses and injuries. Fatigue and risky behaviors such as intoxication or drug use result in injuries, including those associated with poor decision-making.

Lastly, the construction workers mentioned the value of hearing the stories of the older, more experienced workers to gain situational awareness and heighten their ability to recognize hazards.

Sharing stories allows others to learn from their fellow workers.

Sharing stories allows all of us to learn the lessons near misses can teach us.

Reference: Santiago K, Yang X, Ruano-Herreria EC, Chalmers J, Cavicchia P, Caban-Martinez, AJ. “Characterising near misses and injuries in the temporary agency construction workforce: qualitative study approach.” Occup Environ Med 2020;77:94-99.

Ann Backus, MS, is the director of outreach for the Harvard School of Public Health’s Department of Environmental Health in Boston, MA. She may be reached by phone at (617) 432-3327 or by e-mail at <abackus@hsph.harvard.edu>.