The fishing industry, as we all know, was hit hard beginning this past March when the COVID-19 pandemic really took hold in the US.

While federal and state governments identified and designated fishing as an “essential industry” – one that could remain open while others had to shut down – the supply chains associated with fishing were severely disrupted and, to a great extent, remain so.

There was no market demand for fish. Restaurants were shut down, grocery stores were not buying fresh product, and processing plants could only handle so much.

In this column I want to explore whether we can see the pandemic’s economic impact on the fishing industry by comparing District I Coast Guard data during the periods from Jan. 1 to Jun. 15 for both 2019 and 2020.

I subsequently then reanalyzed the data for just the months beginning when the COVID-19 shutdown began.

The issue is not whether there has been, or is, economic impact on fishermen and their families as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. There certainly was and is.

The attempt here is to see if we can use the Coast Guard incident database to further detect and define the economic impact.

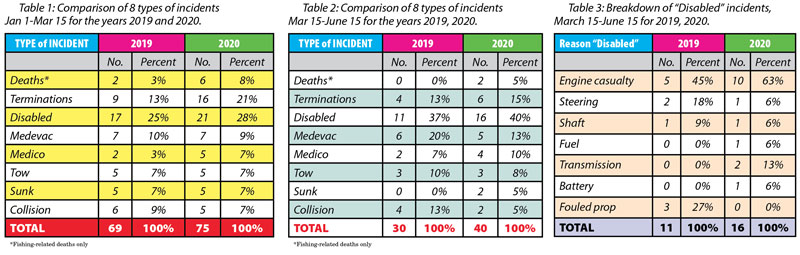

Table 1 compares a subset of incidents which the Coast Guard responded to during the period Jan. 1 through Jun. 15 in 2019 and 2020.

In terms of raw numbers, there was a total of six more incidents during the period Jan. 1-Jun. 15 in 2020 than in 2019.

This includes more of each of the following incidents in 2020: deaths, terminations, disabled vessels, and medico incidents.

However, the year-over-year differences in the numbers of specific incident types are small and not remarkable.

So, is it a different story if we look at only the period Mar. 15 through Jun. 15 for 2019 and 2020?

Table 2 compares a subset of incidents which the Coast Guard responded to during the period Mar. 15 through Jun. 15.

There was a total of 10 more of these particular incidents in 2020 (30 in 2019 and 40 in 2020), but the percentage of each type of incident was roughly comparable year-to-year.

The story becomes a little more interesting when we break down the reasons given for disabled vessel incidents.

In 2019 and 2020, both during the Jan.-Jun. time frame and the Mar.-Jun. time frame, incidents termed “disabled” make up the highest percentage of incidents as shown in Tables 1 and 2.

As Table 3 shows, there were twice as many engine casualties in 2020 as in 2019 during the Mar.15-Jun. 15 period.

As a percentage of total disabled incidents, 45% were due to engine casualties in 2019, whereas 63% were engine casualties in 2020.

Combining the 10 engine casualties with the 2 transmission casualties we have 12 of 16 incidents being engine-related in 2020, or 75% of the total.

Obviously engine and transmission maintenance and repair are costly items for fishermen.

Can we infer that reduction in income due to the COVID-19 lockdown could account for the increase in engine and transmission failures?

With 75% of the disabled incidents in 2020 being related to costly maintenance items, can we say that lost income is possibly to blame here?

Well, the answer, after all this figuring out, may surprise you.

It turns out that of the 16 disabled incidents in 2020, three occurred with the same vessel, the fishing vessel Capt. T, a 72’ steel scalloper.

One engine casualty and both transmission incidents belong to Capt. T.

If we count that vessel only once, not three times (because it is one income producer), then the engine-related incidents add up to 10 and the total number of incidents drops to 14.

This change drops the percentage to 57% and is just a few percentage points over 50%, just as the 2019 percentage of 45% is a few points below 50%.

The bottom line is, that in this small window of time at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, it does not seem feasible to use the Coast Guard incident database as an indicator of economic impact.

If that was your thought when you started reading this article, you were right.

Hats off to fishermen for not short-changing safety at this time of economic hardship.

None of the big-ticket items – such as missing or expired liferafts – that could result in a termination, showed up as a termination reason in the period from March to June this year.

Either fishermen were making sure they had safety equipment or they simply weren’t going out.

It would seem that we will have to look to the landings data and market value later this year in order to get a true indication of the economic impact of the COVID-19 shutdown

on the fishing industry.

I’ll leave that up to the economists and market analysts.

In the meantime, as the pandemic restrictions are being gradually lifted, things are opening up, and many of you are fishing harder and longer, be safe and be smart.

Resist the temptation to take undue risks in an effort to make up for lost fishing time earlier this year.

Ann Backus, MS, is the director of outreach for the Harvard School of Public Health’s Department of Environmental Health in Boston, MA. She may be reached by phone at (617) 432-3327 or by e-mail at <abackus@hsph.harvard.edu>.